Long-distance relationships for endangered corals

Researchers use cryopreserved sperm to import genetic diversity that could help corals adapt to climate change

8 September 2021

‘Corals are a vital foundation species for reef ecosystems,’ said Iliana Baums, professor of biology at Penn State and one of the leaders of the research team. ‘Reefs provide habitat for astonishing species diversity, protect shorelines, and are economically important for fisheries, but they are suffering in many places due to warming ocean waters. Without intervention, we will continue to lose corals to climate change with potentially disastrous consequences.’

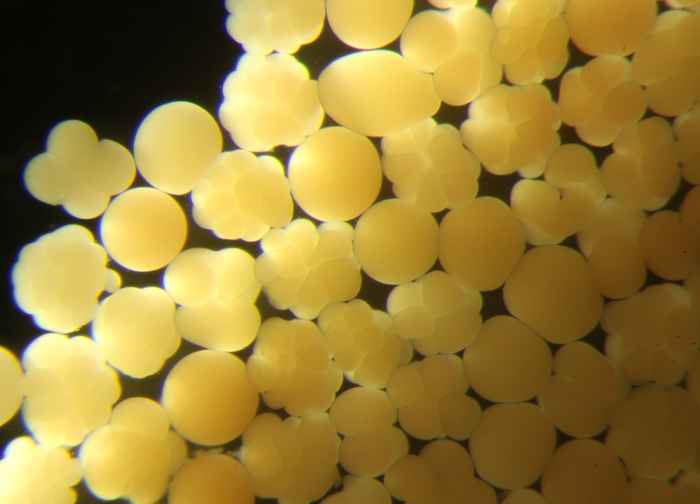

Most corals only attempt sexual reproduction once a year and the eggs and sperm are only viable for a short time period. Cryopreservation allows researcher to breed corals with parentage from hundreds of kilometres apart. Most corals reproduce by broadcasting bundles of eggs and sperm into the sea water in a spectacular spawning event timed with the full moon. The researchers collected these bundles from corals in Florida and Puerto Rico, separated the eggs and sperm, and then quickly froze the sperm cells using a liquid nitrogen cryopreservation technique.

‘Because these corals only produce eggs and sperm once per year, frozen sperm collected in Florida and Puerto Rico needed to be cryopreserved in advance and stored for over a year until it could be used for a spawning event in Curaçao,’ said Baums.

‘Overall, 42% of the trans-Caribbean coral offspring survived to at least six months, the highest survival rate ever achieved in this endangered species,’ said Kristen Marhaver, a marine biologist at the CARMABI Foundation in Curaçao and co-corresponding author of the study. These results demonstrate that assisted gene flow could be a valuable tool in conservation by introducing genetic diversity into this critically endangered marine species.

Read the entire article in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)

Assisted gene flow using cryopreserved sperm in critically endangered coral

Mary Hagedorn, Christopher A. Page, Keri L. O’Neil, Daisy M. Flores, Lucas Tichy, Trinity Conn, Valérie F. Chamberland, Claire Lager, Nikolas Zuchowicz, Kathryn Lohr, Harvey Blackburn, Tali Vardi, Jennifer Moore, Tom Moore, Iliana B. Baums, Mark J. A. Vermeij, and Kristen L. Marhaver