PhD defence ceremony by Sarah Solomon

- Date

- 19 February 2026

- Time

- 13:00

- Location

- Agnietenkapel

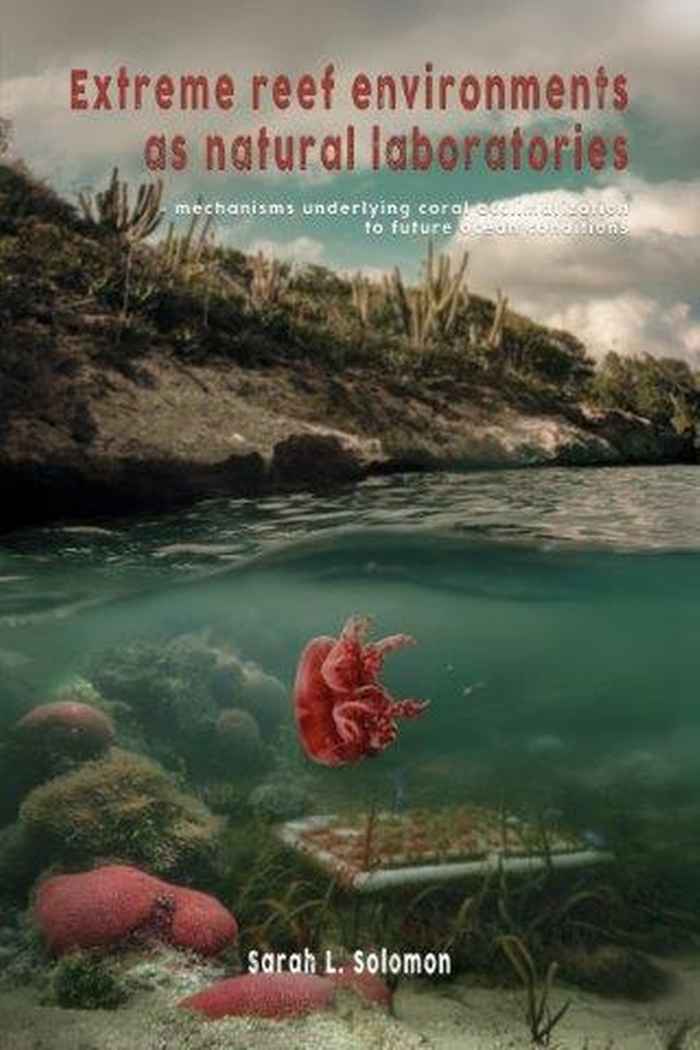

Reef-building corals are under immense pressure to adapt and/or acclimatize to multiple co-occurring stressors, however their capacity to do so remains uncertain. Corals that naturally persist in habitats with extreme, multi-stressor conditions can provide insights into the physiological mechanisms and adaptive capacity of corals under future ocean conditions. We found that three Caribbean coral species from two extreme, variable inland bay habitats had highly dynamic trophic strategies across seasons, associated with stress-tolerant algal symbionts, and harbored potentially beneficial bacterial communities. To assess the acclimatization capacity of corals to novel conditions, two coral species were reciprocally transplanted between an inland bay and an environmentally more stable and benign fringing reef. Following one year of transplantation, we conducted a heat stress experiment to evaluate the effects of acclimatization on coral heat tolerance. Both species from both habitats demonstrated substantial acclimatization capacity to novel conditions, but nonetheless, experienced energetic or fitness trade-offs. While Siderastrea siderea transplanted from the reef to the bay acquired enhanced heat tolerance compared to reef natives, branching Porites did not. Corals native to the bay exhibited greater heat tolerance than conspecifics from the fringing reef, but experienced significant growth trade-offs when transplanted to the reef. Our study demonstrates that reef-origin S. siderea have high adaptive capacity to more extreme conditions, making them potential candidates for restoration initiatives that use stress-hardening approaches. The inland bays are hotspots of thermal resilience, with potential to support proactive coral reef management opportunities, such as inclusion in spatial marine protected area planning.