Pteropods produce thinner shells in more acidified and colder waters

28 January 2021

Pteropods are fat-rich and therefore an important food source for organisms ranging from other plankton to juvenile salmon to whales. They make shells by fixing calcium carbonate in ocean water to form an exoskeleton. Sometimes they are called sea butterflies because of how they appear to flap their ‘wings’ as they swim through the water column.

Carbon dioxide-rich waters

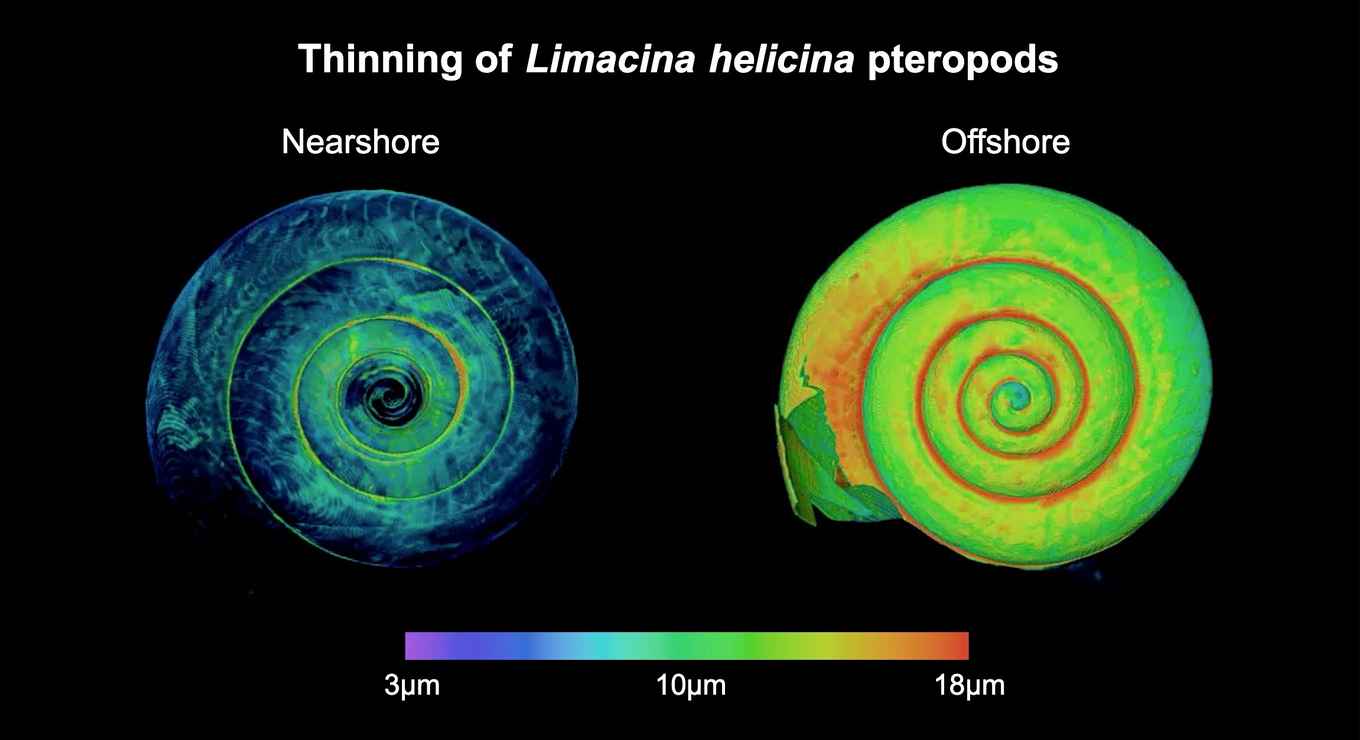

Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, led by a team of Dutch and American scientists, found that the shells of pteropods collected in this upwelling region were 37 percent thinner than ones collected offshore.

‘It appears that pteropods make thinner shells where upwelling brings water that is colder and lower in pH to the surface,’ said lead author Lisette Mekkes, PhD candidate at the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics of the University of Amsterdam and Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Mekkes added that while some shells also showed signs of dissolution, the change in shell thickness was particularly pronounced, demonstrating that acidified water interfered with pteropods’ ability to build their shells.

Research cruise

The scientists examined the shells of pteropods collected during the 2016 NOAA Ocean Acidification Program research cruise in the northern California Current Ecosystem. The shell thicknesses of 80 of the tiny creatures - no larger than the head of a pin - were analyzed using 3D scans provided by micron-scale computer tomography, a high-resolution X-ray technique. The scientists also examined the shells with a scanning electron microscope to assess if thinner shells were a result of dissolution. They also used DNA analysis to make sure the examined specimens belonged to a single population.

‘Pteropod shells protect against predation and infection, but making thinner shells could also be an adaptive or acclimation strategy,’ says Katja Peijnenburg, research scientist at the UvA and Naturalis Biodiversity Center. ‘However, an important question is how long can pteropods continue making thinner shells in rapidly acidifying waters?’

Ocean acification

The California Current Ecosystem along the West Coast is especially vulnerable to ocean acidification because it not only absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but is also bathed by seasonal upwelling of carbon-dioxide rich waters from the deep ocean. In recent years these waters have grown increasingly corrosive as a result of the increasing amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide absorbed into the ocean.

‘Our research shows that within two to three months, pteropods transported by currents from the open-ocean to more corrosive nearshore waters have difficulty building their shells,’ said Nina Bednaršek, a research scientist from the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project in Costa Mesa, California, and coauthor of the study.

Over the last two-and-a-half centuries, scientists say, the global ocean has absorbed approximately 620 billion tons of carbon dioxide from emissions released into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, changes in land-use, and cement production, resulting in a process called ocean acidification.

‘The new research provides the foundation for understanding how pteropods and other microscopic organisms are actively affected by progressing ocean acidification and how these changes can impact the global carbon cycle and ecological communities,’ said Richard Feely, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and chief scientist for the cruise.

This research was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientifc Research and NOAA’s Ocean Acidification.

Publication details

Lisette Mekkes, Willem Renema, Nina Bednaršek, Simone R. Alin, Richard A. Feely, Jef Huisman, Peter Roessingh & Katja T. C. A. Peijnenburg: ‘Pteropods make thinner shells in the upwelling region of the California Current Ecosystem,’ in Scientific Reports (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81131-9