Laser scanning data provide insight into butterfly microhabitats

22 April 2021

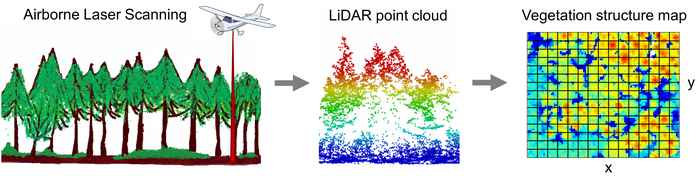

Light Detection And Ranging (LiDAR) is a remote sensing technique that can produce highly detailed 3D data of the landscape. These data are collected by an airplane flying over the landscape with a laser scanner. The distance and position of all the points where the laser reflects from the landscape are measured and used to produce a point cloud of the landscape: a three-dimensional image of the terrain, human constructions and the vegetation structure. The Dutch waterboards use this technique to produce the national elevation model of the Netherlands (the AHN). For this purpose, reflections of the vegetation structure are irrelevant, but for ecologists they provide the opportunity to investigate the structure of the vegetation in high resolution and across the whole of the Netherlands.

Researchers from the UvA Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics and the Dutch Butterfly Conservation have used LiDAR data to identify the fine-scale habitat preferences of butterflies. They did this for four threatened species: Small pearl-bordered fritillary, Grayling, White admiral and Heath fritillary. These species occur in contrasting habitats: moist grasslands, dry open habitats, moist forests and dry forests with clearings. This selection allowed a comparison of the applicability of LiDAR data across different habitats. Using data from the Dutch butterfly monitoring scheme, locations were compared where a species was present with locations where it was absent. The Dutch national LiDAR dataset AHN3 (commonly available via Ahn.nl) was used to classify the vegetation structure at each sampling point.

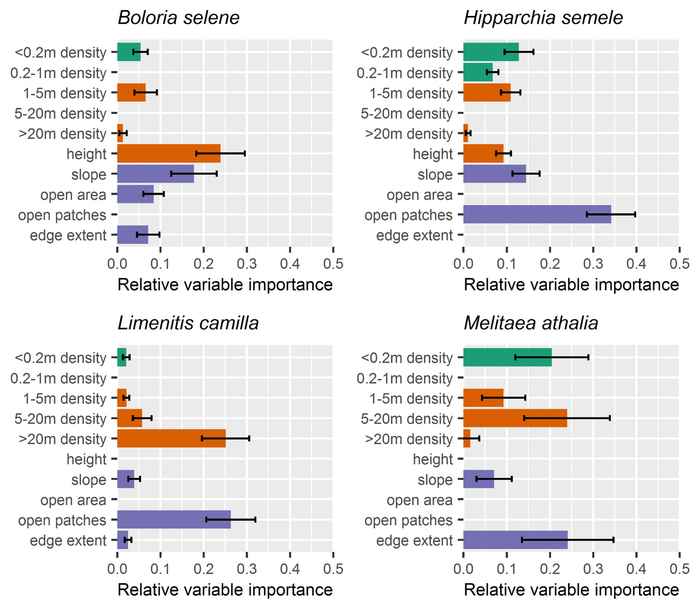

The vertical and horizontal structure of the vegetation were important determinants of the occurrence of these four butterfly species. Landscape-scale structures and the mean height of the vegetation where the most important characteristics for both open habitat species (the Small pearl-bordered fritillary and the Grayling), while the density of mid-to-high vegetation and the number of open patches were most important for both woodland species (the White admiral and the Heath fritillary). The models also provided new ecological insights; for instance, the presence of high trees (higher then twenty metres) appears to be important for the White admiral. Wooded habitats could be classified better than open habitats, because low and seasonal vegetations such as grasses and herbs are less well captured in the LiDAR data than higher permanent vegetation.

With the use of LiDAR data we can now explore which vegetation structures are important for specific species, which can be used to map suitable areas or to improve nature management at existing habitats. This can also be done for many other invertebrate species as long as detailed distribution data are available. The potential of LiDAR data will increase further in the future when more detailed and more frequent LiDAR data become available. For example, the current data are collected in winter when a better reflectance of the surface can be obtained due to the absence of leaves, but additional data collection during summer could greatly improve the classification of especially grassland vegetations. LiDAR data thus offer a great potential to study the fine-scale habitat preferences of invertebrates.

Publication details

Jan Peter Reinier de Vries, Zsófia Koma, Michiel F. Wallis de Vries, W. Daniel Kissling: 'Identifying fine‐scale habitat preferences of threatened butterflies using airborne laser scanning,' in Diversity and Distributions (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13272