Fireworks have long-lasting effects on wild birds

28 November 2022

Every year, fireworks are set off around the world to welcome the new year. This nighttime spectacle of light, colour and sound is enjoyable for humans, but less so for animals. As anyone with a pet knows, the combination of loud bangs, bright lights and smoke can provoke fear and disorientation in animals.

Over the past decade, studies in Europe have begun to uncover some of the negative impacts of fireworks on wild birds. A study from 2011, for instance, used weather radar to show that thousands of birds in the Netherlands erupted into the air at midnight on New Year’s Eve when fireworks began.

But until now, it remained unclear if fireworks also changed important behaviours such as eating and sleeping, and wether or not birds were able to bounce back after the initial disturbance. Now, using GPS-trackers, a team of scientists has for the first time quantified the effects of fireworks on these behaviours in the longer term.

"Shocking to see"

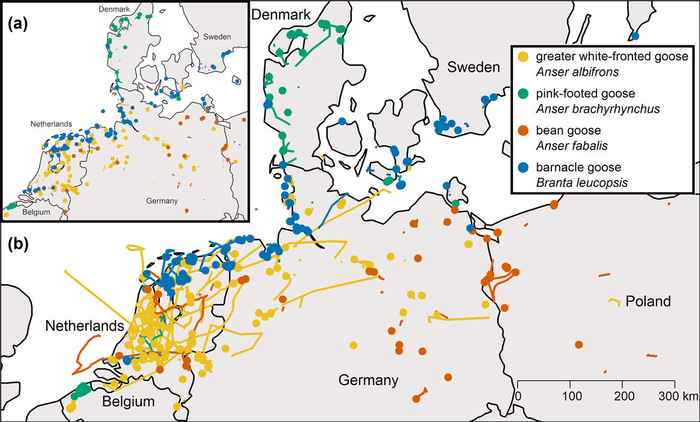

Four species were studied: greater white-fronted, barnacle, pink-footed and bean geese. All are Arctic migratory species, which spend their winters resting and feeding in Northern Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands. GPS information was collected for 347 individuals in the 12 days before and 12 days after New Year’s Eve for eight consecutive years, with each individual tracked for two years on average.

The study’s findings reveal significant changes to the wintering behaviour of all four species in response to fireworks. Normally, geese would return to the same body of water for several nights, resting on the surface and moving very little to save energy. But when the fireworks started on New Year’s Eve, geese left their sleeping sites more often, and flew 5-16 km further and 40-150 m higher on average than on previous nights.

“It's shocking to see just how much further birds fly on nights with fireworks compared to other nights,” says Andrea Kölzsch, a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and first author of the study. “Some individuals flew hundreds of kilometers over a single night, covering distances that they would normally fly only during migration.”

Need to compensate

The team also measured particulate matter (PM) in the air near sleeping sites, and found that PM increased by up to 650 percent on New Year’s Eve at all sites studied. “We found that birds were leaving their sleeping sites and choosing places further away from people, with lower PM, which strongly suggests they tried to escape from the fireworks,” says Kölzsch.

Beyond the immediate response to fireworks, birds also foraged 10 percent more and moved less in the 12 days after New Year’s Eve. "The birds are likely compensating for the extra energy they expended during the night of the fireworks," says Bart Nolet, senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology and final author of the study.

In the final year of the study, the team were offered a unique opportunity to control for the effects of fireworks. The pandemic lockdown of 2020/2021 led to a widespread fireworks ban, and greatly reduced levels of disturbance. Despite this, increased flight activity, distance and altitude were still noticable on New Year’s Eve in two of the four goose species.

“This suggests that even small amounts of fireworks will change the behaviours of geese in ways that might reduce their chances of survival, at least in severe winters,” says Nolet. “In order to provide a safe space for the birds, recreational fireworks should be banned from areas near national parks, bird sanctuaries, and other important bird resting places.”

More information

This text originates from NIOO. The original text can be read here. Prof. dr. Bart A. Nolet is affiliated with the Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics (IBED, UvA) as Special Chair of Waterfowl Movement Ecology.

Scientific paper:

Wild goose chase: geese flee high and far, and with aftereffects from New Year’s fireworks(external link)

Andrea Koelzsch, Thomas Lameris, Gerhard Müskens, Kees Schreven, Nelleke Buitendijk, Helmut Kruckenberg, Sander Moonen, Thomas Heinicke, Lei Cao, Jesper Madsen, Martin Wikelski & Bart Nolet. Conservation Letters, 24 November 2022 (online early view), open access.